Talking gaming: Thierry Baujard on strategies for success in the European gaming sector

By Jon Montes, Research Lead, Strategy & Business Intelligence, and Corinne Darche, Analyst, Strategy & Business Intelligence

The gaming industry continues to drive impressive sales amidst a changing technological and corporate landscape. In Canada, the gaming sector contributed over $5B total to the national GDP and generated over 34,000 full-time equivalents (FTE) in 2024. 1 As global demand grows, how are national funders ensuring local industries remain competitive?

Germany’s SpielFabrique is a catalyst in the European ecosystem, connecting gaming studios and creatives with dozens of countries and funders to grow the independent sector. Co-founder Thierry Baujard sat down with Perspectivesto discuss the state of the industry in Europe and what might lie ahead.

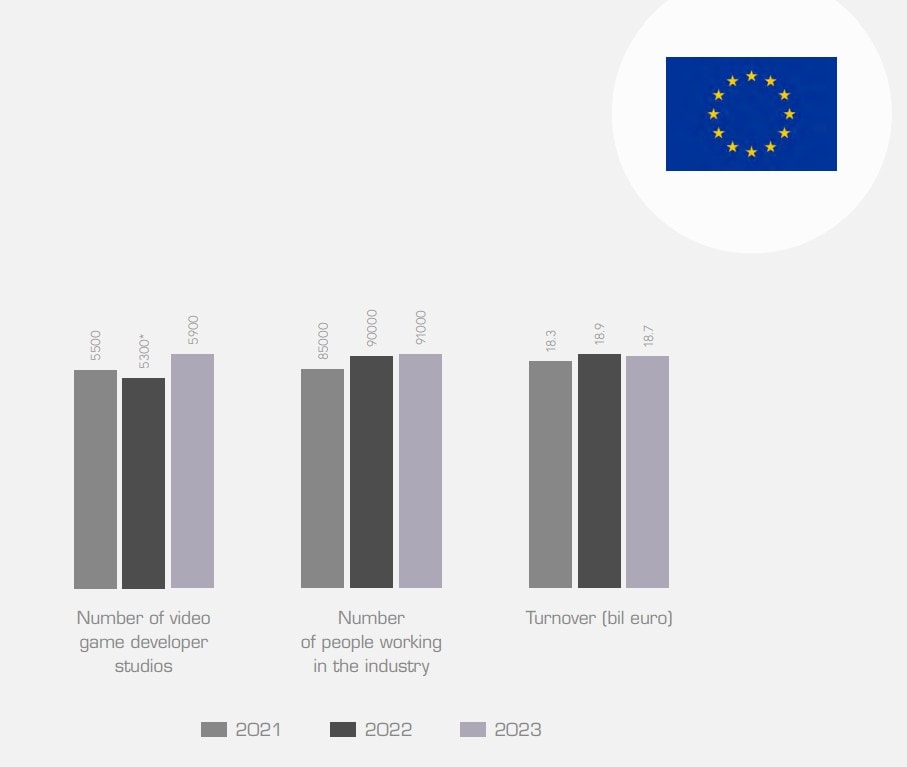

Perspectives: A recent study of European countries 2 totalled their gaming sales at over EUR 19B, or CAD 27B, in 2023. 3 These are impressive numbers, but could you give us a sense of the state of the European video game industry in 2025?

Thierry Baujard: The first thing to understand is that we don’t really have a coherent European ecosystem. There are very different countries with different markets. There are countries that are very developed and there are smaller countries with less structure.

In general, we still have a few big companies that take most of the revenues. These companies are mostly from France, Germany, Sweden, Finland, and also Poland. Those are really the places where you have big studios that drive big revenues. And those countries have a lot of indies [independent studios] too.

You have other countries, especially in central and eastern Europe, with lots of indies but limited national support. At the same time, they also have big studios driven by non-European companies, basically from the U.S. or Russia.

The south is also different. Spain and Portugal are developing a lot of indie studios, and there are a few big companies too. Italy is smaller in terms of support systems compared to its consumer market, which is very big. So that’s a special case.

P: In Canada, like in many European countries, there’s a blend of public and private financing. Some countries, like Sweden, rely more on private-sector financing. Can you talk about the difference between those approaches? How can public funders also leverage private investment?

TB: The rule in Europe is that a maximum of 50 per cent of funding can come from public sources. There are a few exceptions, but it’s rare. So you need private money. Most of that money, until now, has come from publishers. Private investment declined after COVID but is coming back slowly. One of the key questions for me is where does it fit? Do they invest in your company? In your project?

Investment used to be very strongly equity-based—a company’s equity—but now you see many firms offering project-based, revenue-share models as well. Company equity is much more difficult because it’s very difficult to get an exit. All the people who invested equity in companies, in studios, they have a very hard time getting their money back. But in projects, I think it’s a very good way to test the team, test the company, and get some revenue quicker, which is what investors are looking for today.

One thing to mention is that the European Commission, with the European Investment Fund (EIF), have created MediaInvest, which matches private investment with public funds. It’s been a bit slow to start but now we have two or three funds focused on video games that have been developed from that and more will be created. So that will help get more private investment in Europe for games.

P: Are there other structural pieces where public funders can play a role? What are the practical obstacles outside financing?

TB: The main difficulty is that people don’t know each other. That’s why you have a lot of local incubators that are very good at teaching people how to start, how to find a team, how to create a legal company, and helping them develop their first game.

But at some point, it’s a global business and has to be much more international in its thinking. In film, you shoot everywhere but distribution is very local. Games are the opposite—distribution is completely global. Most of the people who will buy your game are based in Asia or the U.S. or South America, not so much in Europe. So there’s a misunderstanding about who is really buying games and how that happens.

So that’s a problem and you don’t really have many European solutions. If you look at film, you have people like Eurimages, who help get people to co-produce together. And with Creative Europe from the European Commission, there are many programs that support markets and training.

This is the work we’ve done with Indie Plaza, our database that outlines what kind of funding is available and where. Before that, many people had no idea. We were also the first to use Creative Europe’s training program for games. Nobody did it before. And now you have a few people doing that, but it’s something that needs to be developed.

P: So what I’m hearing is that there’s an opportunity here.

TB: That’s what we looked at when we started Match, our co-production market. We started with France and Germany because they were the two countries we knew. Since then, many countries have come to take part. For two years now we’ve had Canadian studios attending. So I think there is an appetite, but it’s tough because people don’t have networks. I mean, they know that in Canada there are tax credits and such, but how to use them? They have no knowledge about that. This knowledge transfer is going to take time.

P: While video game development can be quite lengthy, production is certainly the costliest step. In 2024-2025, the CMF contributed over CAD 47M to the interactive digital media (IDM) sector, with the bulk of that in production and the rest for development as well as career accelerators. 4 Given the conversation about public and private funds, where is public investment most effective?

TB: European public funds are very local, very regional. They want to help studios develop ideas and stay in the country. Making a game just with grants is very difficult because most countries don’t have enough money. So the idea for European countries is to develop projects locally and give [studios] the possibility to talk to other people. But that also puts studios at risk—“OK, I’ve got a small concept but now I need a lot of money from a publisher or a private investor.” And then studios might lose some control over the project itself. Soit’s not easy.

Many bigger countries, like France, have strong tax credits that can support production. In Germany it’s not quite a tax credit, but it works similarly. And you have countries like Italy, who created a tax credit but have no development fund. It’s good to have a tax credit but if studios have no development money, they can’t really use the tax credit.

So, yeah, I think there will be a wave of tax credits. France, the U.K., as you know, have them—and Italy, and Ireland. Spain is looking into it. Belgium, of course, has one. Like film, we’re going to see a big wave of tax credits coming all over Europe.

The other part that funds are looking at now is really for marketing and launch. If games are not promoted, you know, nobody will buy them. Some public funds now are looking into that.

P: That covers individual projects, but what about businesses? How are funders supporting companies while ensuring that the right projects also get support?

TB: I think this is lacking in Europe. Most public funds are project-based. But the Banque publique d’investissment (BPI) in France is investing from EUR 20M to EUR 30M [CAD 32.7M to CAD 49M] in studios every year. Not in projects, but in studios.

I think this is really missing if we want to have sustainability. You can’t push people towards project-by-project funding and hope they get the next project financed to cash flow the end of the last one. I think funders need to play with different funding instruments. Another problem we have in Europe is the lack of banking options for gaming studios. In film, you have banks who help with cash flow and gap financing. This is missing in games.

So you need all these different instruments, you need corporate support, you need project financing, and you need mechanisms to deal with debt. If you don’t have all those, the ecosystem can’t really work in a very efficient, or let’s say healthy, way.

In Europe, there also are fewer and fewer publishers now, and their capital is very limited. So for public funds, I think they should really support publishers as well.

P: One of the stories to come out of GamesCom last August was how artificial intelligence (AI) might help reduce the time it takes to develop and create games. 5 In Canada we know that 48 per cent of Canadian companies are using it, and more intending to do so. 6 What questions does this pose?

TB: Studios are using AI for sure, though it’s difficult to know how much they’re using it. It will grow—that’s for sure. For funders, I don’t think we really have an answer yet. I think it’s potentially reducing the cost of production and development, which could help in facilitating financing.

The question for funders is what will AI mean for the cultural impact they are expecting? If you start using algorithms to develop your game that look at what the world is, the game can start to lose its cultural specificity. At the same time, if they are not so specific, maybe there’s more commercial appeal? It needs to be discussed more.

Whether public funding for games is cultural or economic or about technology, everybody here agrees it’s somewhere in between. What’s good in Europe is that we have different ways of looking at things, though it’s a bit confusing for people and studios to understand where the emphasis is. That’s something we’re starting to discuss within the Game Public Fund Network we set up 18 months ago, but we’re really at the beginning. We now have twelve countries taking part in that network to exchange best practices for public funding in games.

P: What’s next for you and for SpielFabrique?

TB: We call ourselves a catalyst for the game ecosystem, and I think it’s really helping different studios and countries work together. We’re building pan-European acceleration programs, and have had a very interesting expansion outside Europe, which honestly we weren’t really prepared for. Building relationships with Canada, of course, Brazil, and some African countries. It’s very interesting. And then all these cross-sectoral relationships are very important for us because we see that people outside the gaming industry don’t really understand it. Other sectors like film and music, I think they can benefit a lot from what games are all about, which is communities and engagement.

Interview edited for length and clarity. Conducted September 23, 2025.

FOOTNOTES

- “Canada’s Video Game Industry: Powering the Future of Play.” The Entertainment Software Association of Canada, Nordicity, January 2025, p. 11, 22, https://theesa.ca/resource/canadas-video-game-industry-2024/.

- Note that in this report, the European countries considered were Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden.

- “2023 European Video Games Industry Insight Report.” European Games Developer Federation, 12 August 2025, p. 11, https://www.egdf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/2023-European-video-games-industry-insight-report.pdf.

- “Build Different: CMF 2024-2025 Annual Report.” Canada Media Fund, p. 54, https://cmf-fmc.ca/document/2024-2025-annual-report/.

- Packwood, Lewis. “At Gamescom, it felt like the industry now has a plan: make games quicker.” GamesIndustry.biz, 22 August 2025, https://www.gamesindustry.biz/at-gamescom-it-felt-like-the-industry-now-has-a-plan-make-games-quicker-opinion.

- “Canada’s Video Game Industry: Powering the Future of Play.” The Entertainment Software Association of Canada, Nordicity, January 2025, p. 30, https://theesa.ca/resource/canadas-video-game-industry-2024/.