From K-Policy to K-Brand: Making a content powerhouse

By Jon Montes, Research Lead, Strategy & Business Intelligence, and Irene Berkowitz, Senior Research Consultant, Strategy & Business Intelligence

South Korea has seized the world stage and garnered billions of dollars riding the crest of a Korean wave across music, movies, TV, animation, and video games, not to mention the popularity of Korean fashion, technology, automobiles, beauty, and cuisine. And they’re just getting started.

In summer 2025, South Korea’s new minister of culture, sports, and tourism, Chae Hwi-young, made headlines by promising to nearly double the output of the culture industry from KRW 154T to KRW 300T (approx. CAD 300B). With the popularity of K-Content, the Minister views the sector as a “core national industry” 1 with the power to drive GDP.

South Korea’s cultural export success and prestigious national brand are the result of a 1990’s pivot away from protectionist strategies, followed by a series of policy decisions. This spurred competition and created unprecedented demand for Korean content, ultimately laying the groundwork for a national industry with international clout.

Content: A national industry

1993 was a turning point. After the release of the US blockbuster Jurassic Park, a government working group used the film to demonstrate the connection between culture and economic benefits. Then-President Kim Young-sam remarked that the film’s profit represented the equivalent of selling 1.5 million Hyundais, one of South Korea’s most successful auto brands. 2

On a conceptual level, the President’s remarks underscored the value of film and TV products as economic drivers. More practically, he set in motion a strategy of establishing production studios and giving them key financial instruments that promoted corporate stability and growth. With a nod to their automobile and tech industries, the government classified media production as part of the country’s manufacturing sector. This gave studios practical tools—for instance, the ability to access bank loans and subsidies—that set them up as sound corporate entities. 3

The strategy saw results, particularly in the rapid growth of a Hollywood-like structure built mostly on private financing, followed by successful exports to China and across Asia. 4 After 1995, Korean content exports increased fortyfold in less than two decades, 5 a financial success that accelerated the Korean wave.

Today, South Korea uses the term “content industry” rather than “cultural industry,” emphasizing the “tradable outputs produced by the sector” over less tangible, creative ones. 6 While some were initially skeptical that creating content for export would diminish cultural contribution, Korean content “is now seen as a manifestation of national culture and as a means to preserve and strengthen the cultural identity of the Republic of Korea.” 7

However, the path to global success wasn’t entirely linear.

Engineering demand through competition

Engineering South Korea’s media success took decades. With a relatively small population (51 million as of today) compared to neighbouring Japan and China, producers struggled to turn a profit through domestic sales alone. Content had to compete at home and abroad.

The deregulation of TV broadcasting may have been the most significant policy in kickstarting the Korean wave. During the 1990s, imported Japanese content was perceived as a threat to the domestic market and was heavily restricted. With the post-Jurassic Park shift in strategy, the government made the bold decision to reverse that prohibition, asserting “protection-oriented policy is […] likely to hold Korea back from learning and contributing to international cultural trends.” 8 Now, Korean producers had to compete for audiences used to foreign content and creativity flourished. As Korean exports increased throughout Asia, they were eventually exported to Japan, flipping the previous dynamic and reaching a market once considered impenetrable.

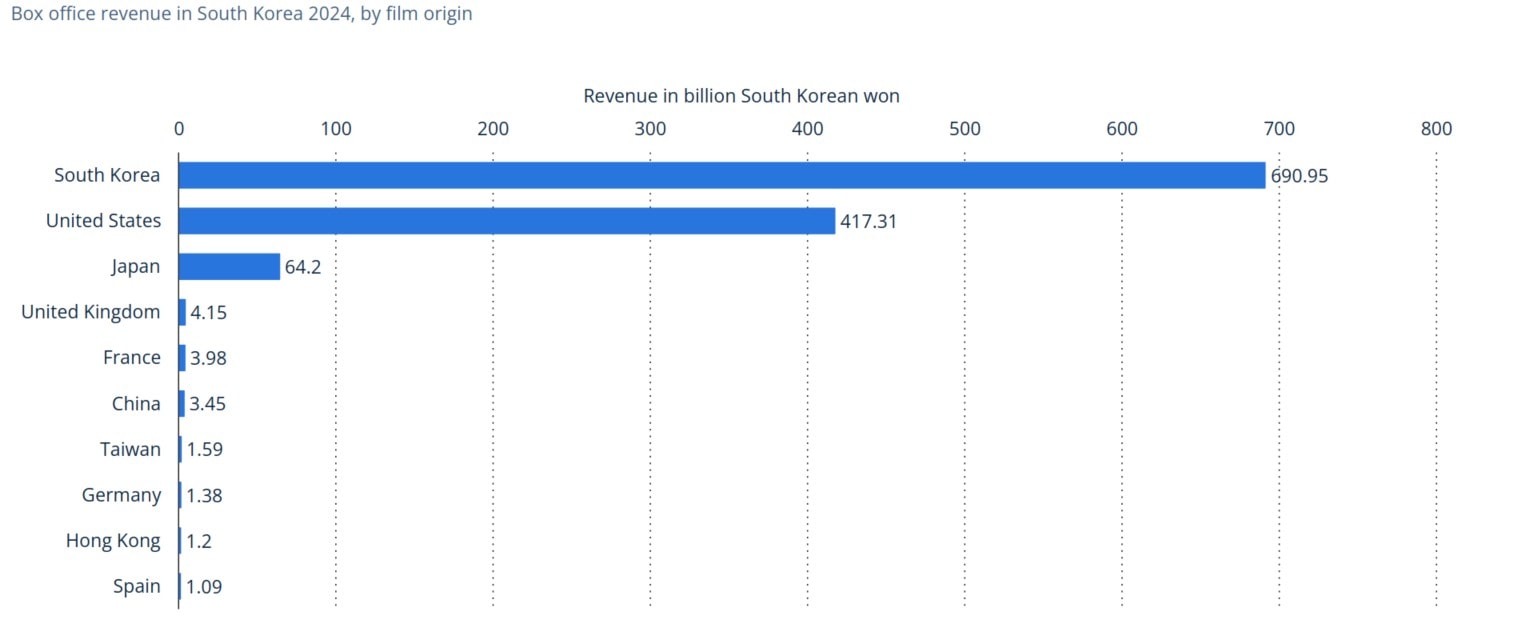

A similar policy pivot happened in the theatrical sector. 9 To protect Korean films, a screen quota had been put in place, at its peak requiring films to spend 146 days in theatres. In 2006, under pressure during trade negotiations with the United States, South Korea halved that quota to 73 days, sparking high-profile protests and predictions that Korean cinema would be diluted. 10 While the country offset some of this criticism by announcing additional sector funding, 11 the fear ultimately did not materialize. In 2023, Korean films earned 48.5 per cent of the domestic box office, fifth highest in the world behind India, the U.S., Japan, and China, and ahead of any European country. 12 13 That figure jumped to 58 per cent in 2024, generating over KRW 690B (approx. CAD 678M). 14

Funding incentives also played an important role in building the K-Brand across the screen industries. In 1999, the Basic Law for Promoting Cultural Industries established funds and tax credits to increase investment in high-quality cultural content, co-productions, marketing, and export. 15 In 2018, the Game Industry Promotion Act allocated funds and tax credits to strengthen the video game sector, including research, development, and export marketing.

With the streaming era in full swing, Korean broadcasters have made savvy moves to compete with multinational platforms for domestic audiences. While Netflix remains on top with 8.2 million Korean subscribers, 16 domestic rival Tving has been steadily gaining by leveraging its strong roots in domestic content. 17 The pending merger between Tving and Wavve, another domestic streamer, will create a merged platform with over 9 million subscribers, a serious competitor to Netflix. 18

Leveraging resources to meet unprecedented demand

Backed by three decades of policy, the Korean wave became unstoppable across music, movies, drama, and video games. Pinkfong’s “Baby Shark Dance” is YouTube’s most watched video; another Korean video, K-Pop star Psy’s “Gangnam Style” previously held the record. 19 Bong Joon-ho’s theatrical hit Parasite made history in 2020, winning Academy Awards for both Best Picture and Best International Feature. Squid Game is Netflix’s most watched series. 20 PUBG, the award-winning video game/esports franchise from South Korea’s Krafton Inc, has earnings in excess of USD 10B. 21

Doubling down on this success, as promised by Minister Chae Hwi-young, will require increased international presence and new partnerships. Agencies such as the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) have focused on spurring continued global interest in Korean culture—and by extension investment in K-Content—around the world. In 2019, KOCCA opened its first international centre in France. It now has 24 business centres in cities across the world (including Toronto) with more planned to open. 22 For producers, the Asian Contents and Film Market (ACFM) recently widened its focus from sales to “fostering international co-productions and co-financing opportunities.” 23 In 2025, Korea was the inaugural country of honour at the Banff World Media Festival, and a Canadian producer delegation participated in the ACFM. These exchanges signal cultural alignment and goodwill, though results may take time as producers learn to navigate the structural differences between the two sectors. 24

Ultimately, further expansion will require new tools. Minister Chae recently highlighted the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) as a transformational moment for Korea. He pledged to integrate AI within the entirety of the country’s cultural sector and “establish an innovation strategy for AI content creation, production, and distribution.” 25 In line with South Korea’s tradition of technological adoption, digital innovation will undoubtedly open new opportunities for the country.

Nevertheless, the minister has acknowledged some very practical hurdles to achieving his audacious goal.

One challenge is to ensure the domestic industry retains the financial rewards of the K-Brand. KPop Demon Hunters, 2025’s breakout hit—the most watched film on Netflix at the time of writing—is based on a concept by Canadian-Korean director Maggie Kang, developed by Sony, and distributed by Netflix. In Kang’s opinion, the film’s success “tells us how far Korean culture has come and how big of a cultural force we have become.” 26

Discussing the film in his confirmation hearing, however, the minister noted the dissonance of it being made and distributed by multinational brands rather than through the Korean industry, identifying a need to increase studio capacity. He stated: “We need to look closely and urgently at how we can independently create high-quality films, distribute them globally on a broad scale, and build a sustainable ecosystem where those profits are reinvested into producing even better works.” 27

And while the Tving-Wavve merger will create a formidable domestic streamer, it has also effectively put a freeze on commissioning new content until the merger is approved—a trend that aligns with the general growing pains of the global streaming industry. 28 Combined with rising production costs, meeting unprecedented demand for Korean content and doubling revenues looks to be an ongoing, if enviable, challenge for the new minister.

FOOTNOTES

- Park, Ga-young. “Tech and media expert Chae Hwi-young emphasizes the use of AI.” The Korea Herald, July 29, 2025, https://www.koreaherald.com/article/10542318.

- Jeon, Won Kyung. The ‘Korean Wave’ and television drama exports, 1995-2005. 2013. University of Glasgow, PhD dissertation, pp. 77-78, https://theses.gla.ac.uk/4499/.

- Parc, Jimmyn. “A Retrospective of Korean Film Policies: Return of the Jedi.” European Centre for International Political Economy, July 2014, p. 17, https://ecipe.org/publications/retrospective-korean-film-policies-return-jedi/.

- Cho, Hanna. Personal interview. October 6, 2025.

- Jeon, p. 12.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “K-Content Goes Global: How Government Support and Copyright Policy Fuelled the Republic of Korea’s Creative Economy.” United Nations, March 21, 2024, p. 2, https://unctad.org/publication/k-content-goes-global.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- Jeon, p. 112.

- Parc, p. 17.

- Lee, Seoho. “South Korea’s Film Rules Need a Reboot.” Foreign Policy, July 10, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/10/south-korea-film-movie-industry-screen-quota-protectionism-free-trade-covid/.

- Yi, Ch’ang-ho. “South Korean Screen Quota Halved.” KOFIC, February 3, 2006, http://www.koreanfilm.or.kr/eng/news/news.jsp?blbdComCd=601008&seq=344&mode=VIEW..

- “Statistics – Content.” Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (Government of the Republic of Korea), https://www.mcst.go.kr/english/statistics/statistics.jsp?pType=02. Accessed August 14, 2025.

- For reference, Canadian films represented 3.3 per cent, or $29M, of the total Canadian box office. See “Profile 2024.” Canadian Media Producers Association, p. 99, https://cmpa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Profile-2024-ENG-Final.pdf.

- “Film Industry in South Korea.” Statista, p22, 2025, https://www.statista.com/study/60611/film-industry-in-south-korea/.

- Jeon, p. 110.

- Ramachandran, Naman. “‘Squid Game’ Season 3 Powers Netflix Lead as Korea’s Premium VOD Market Hits $1.1 Billion, Report Finds.” Variety, August 13, 2025, https://variety.com/2025/tv/news/squid-game-netflix-korea-premium-vod-market-1236489101/.

- Ramachandran, Naman. “‘Squid Game’ Powers Netflix in Heated Korean Streaming Wars as Tving Closes Gap, New Data Reveals.” Variety, February 17, 2025, https://variety.com/2025/tv/news/squid-game-netflix-tving-korea-streaming-wars-1236310890/.

- Ramachandran, “‘Squid Game’ Season 3 Powers Netflix Lead.”

- Ceci, Laura. “Most viewed YouTube videos of all time 2025.” Statista, February 17, 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/249396/top-youtube-videos-views/.

- Corbett, Erin. “Squid Game Season 3 Takes Over with Record-Breaking Global Debut at No. 1.” Tudum by Netflix, July 1, 2025, https://www.netflix.com/tudum/articles/top-10-june-23-2025.

- Curry, David. “PUBG Mobile Revenue and Usage Statistics (2025).” Business of Apps, January 22, 2025, https://www.businessofapps.com/data/pubg-mobile-statistics/.

- Yoon So-yeon. “Gov’t to open six new culture business centers in Europe by end of the year.” Korea JoongAng Daily, October 30, 2024, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2024-10-30/culture/lifeStyle/Govt-to-open-six-new-culture-business-centers-in-Europe-by-end-of-the-year/2166916 .

- Park, Sooyong. “PGK launches International Co-production Hotline at KOFIC Co-hosted Producer Hub.” Korean Film News, October 18, 2024, https://www.koreanfilm.or.kr/eng/news/news.jsp?blbdComCd=601006&seq=6174&mode=VIEW.

- Cho, Hanna. Personal interview. October 6, 2025.

- Park, “Tech and media expert Chae Hwi-young emphasizes the use of AI.”

- Kim, Ji-Ye. “In ‘KPop Demon Hunters,’ Maggie Kang brings genre out of its comfort zone.” Korea JoongAnd Daily. June 26, 2025, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2025-06-26/entertainment/movies/In-KPop-Demon-Hunters-Maggie-Kang-brings-genre-out-of-its-comfort-zone/2339481. Accessed September 2, 2025.

- Park, “Tech and media expert Chae Hwi-young emphasizes the use of AI.”

- “TVing, Wavve mega-merger puts freeze on South Korean commissions.” C21 Media, 18 September 2025, https://www.c21media.net/news/tving-wavve-mega-merger-puts-freeze-on-south-korean-commissions/.